With a rich background spanning construction, design, and architecture, Luca Calarailli has built a career at the intersection of the physical and digital worlds. His passion for technology has positioned him as a leading voice on how artificial intelligence is not just an abstract concept but a practical, transformative force in facilities management. He advocates for a future where buildings are not merely static structures but adaptive ecosystems, amplified by data and intelligent automation. In our conversation, we explored the journey from AI readiness to tangible results, touching upon the importance of a clear strategy, the nuances of data integration, and the practical applications transforming daily operations. We also looked ahead to the “North Star” of facilities management, envisioning a time of autonomous buildings and predictive, data-driven strategic planning.

The article stresses treating AI as a business initiative, not just a tech project, and forming a cross-functional task force. Can you share an anecdote of how an FM leader successfully clarified their “why” for AI and what key metrics they used to achieve organizational buy-in?

Absolutely. I worked with a facilities director for a large life sciences campus who was facing immense pressure to cut operational costs without disrupting sensitive research environments. Instead of just pitching “AI for efficiency,” she framed her “why” around risk mitigation and business continuity. Her core problem was that an unexpected HVAC failure in a lab could ruin months of research, costing millions. So, she formed a task force with IT, legal, and their primary FM service provider. Their goal wasn’t just to install sensors; it was to guarantee system uptime in critical areas. They moved away from tracking simple work orders and instead focused on quantifiable, outcome-based metrics like a 99.9% uptime for specific HVAC units and maintaining precise indoor air quality thresholds. By presenting the initiative as a way to protect the company’s core R&D assets, she secured buy-in. The AI wasn’t the product; the product was uninterrupted science, and that’s a language everyone in leadership understood.

You mention that many FM systems operate in silos, leading to poor data quality. For a leader just starting out, could you walk us through the first few steps of conducting a data audit and what tools or processes are essential for integrating these disparate data sources?

It’s a challenge I see constantly, this feeling of being data-rich but information-poor. The first step is to resist the urge to boil the ocean. Don’t try to audit everything at once. Pick one high-value goal, like the predictive maintenance example. The audit then becomes a focused hunt: what data do we need to predict an HVAC failure? You’ll find it scattered—vibration data in the building management platform, repair history in the work order system, and maybe energy consumption logs in a separate utility portal. You have to pull these threads together. The initial process is often manual, just getting the data into a single spreadsheet to assess its quality. Is it clean? Is it structured consistently? Once you prove that connecting these dots provides a valuable insight, you can invest in integration tools. You don’t need a massive, complex data lake from day one. Simple API connectors or a focused data visualization platform can be the critical bridge to connect those islands of information and start building a reliable foundation.

Predictive maintenance for HVAC is a great starting point. Beyond that, what is a less obvious but high-impact asset where you’ve seen AI deliver significant ROI, and what specific data points or sensor readings were most critical for that success?

Elevators. They are the circulatory system of a tall building, and a failure is a massive bottleneck and a serious safety concern. While HVAC gets a lot of attention, applying AI to elevator maintenance has a profound impact. The most critical data points aren’t just about whether it’s running or not; they are far more subtle. We’re talking about high-frequency vibration analysis from sensors placed on the motor, precise tracking of power consumption during ascent and descent, and even acoustic monitoring to detect changes in the sound of the machinery. An AI model can pick up on a minuscule increase in motor vibration or a slight lag in door closing times that no human would ever notice. These are the earliest whispers of a potential failure, allowing a technician to be dispatched for a proactive repair overnight, completely avoiding a chaotic, primetime shutdown with people trapped inside. The ROI isn’t just in avoiding a costly emergency repair; it’s in preserving the trust and safety of every person in that building.

Regarding space utilization, the article discusses combining sensor data with access logs. Can you detail the process for setting this up while addressing privacy concerns, and share some specific examples of how the resulting insights have led to measurable cost savings or improved user satisfaction?

This is an area where you have to lead with transparency. The process begins with a clear policy developed in partnership with IT, HR, and legal. It’s crucial to communicate that the goal is to understand how spaces are used, not track people. We achieve this by using anonymized, aggregated data. For instance, we might combine access control logs—which just show a badge was swiped at a main entrance—with simple, non-camera-based occupancy sensors in meeting rooms that only provide a headcount. These sensors use passive infrared or thermal imaging; they can’t identify anyone. The data is anonymized before it even hits the analytics platform. I saw this work beautifully at a corporate campus that was struggling with complaints about a lack of meeting rooms. The AI-powered analytics revealed that most large conference rooms were being used by just two or three people. By right-sizing the environments—converting a few large, underused rooms into several smaller huddle spaces—they not only eliminated the booking friction and improved employee satisfaction, but they also significantly cut energy and cleaning costs for those repurposed areas.

You describe future “Facilities Command Centers” overseeing autonomous operations. Could you paint a picture of a typical day for an FM professional in this environment? What new skills will be most crucial for them to thrive as they shift from reactive problem-solvers to strategic overseers?

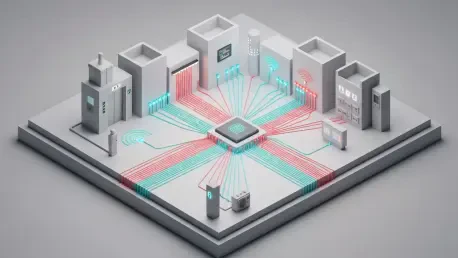

Imagine a Facility Strategist walking into a command center. Instead of a phone ringing off the hook, she’s looking at a dashboard of dynamic digital twins representing her entire building portfolio. The AI has already triaged everything. It might flag that Building C’s energy consumption is trending 8% higher than its historical model predicts for the current weather and occupancy. The system has already run simulations and suggests the most likely cause is a damper that’s stuck open. It’s even scheduled a work order and dispatched a technician for the next low-occupancy window. The strategist’s job is to provide oversight, to ask the bigger questions. She might use the digital twin to simulate the impact of a proposed office reconfiguration on airflow and energy use, or compare her portfolio’s performance against peer institutions. The most crucial skills will be data literacy, strategic thinking, and the ability to manage systems, not just fix problems. They’re moving from being mechanics to being pilots, using intelligent tools to navigate their facilities toward optimal performance.

The text presents a clear path from readiness to implementing pilot projects. What are the most common pitfalls or roadblocks you see organizations encounter when trying to move from assessment to action, and how can they overcome them to build those crucial early success stories?

The single biggest roadblock is the pursuit of perfection. I see so many organizations get stuck in “analysis paralysis,” trying to create a flawless, enterprise-wide AI strategy and a perfectly unified data lake before they even begin. They spend a year planning and have nothing to show for it. The second common pitfall is failing to build a cross-functional coalition from the start. If the FM team champions a project without getting IT and legal on board early, it will hit a wall the moment it touches network security or data privacy. The most effective way to overcome these hurdles is to start small but think big. Identify one specific, high-visibility pain point—like energy waste in a particular building or frequent breakdowns of a critical asset. Launch a discrete pilot project aimed squarely at solving that one problem. When you can go back to leadership in three months with a measurable success story and a clear ROI, you build the trust and momentum needed to scale your efforts and tackle the next challenge.

What is your forecast for how quickly AI-driven digital twins and predictive capital planning will move from being “North Star” concepts to becoming standard, expected practice in the majority of commercial facilities?

I believe we are looking at a five-to-seven-year horizon for these technologies to become standard in new and Class A commercial properties, with broader adoption across the industry in the decade that follows. Right now, they feel like a futuristic “North Star,” but the foundational elements are rapidly becoming commoditized. The cost of IoT sensors is dropping, and cloud computing makes the necessary processing power more accessible than ever. The real accelerator won’t just be the technology, but the profound shift in the business conversation. When a facilities executive can move from requesting a budget based on a 20-year-old replacement schedule to presenting a predictive model showing the precise, data-driven ROI of replacing a chiller fleet in year 17 versus year 20—factoring in projected energy costs, maintenance savings, and risk mitigation—they fundamentally change their role. They become a strategic financial partner. That level of influence is so powerful that once a few leaders in the market start doing it, it will quickly become the expected standard for everyone else.