The subtle, often unconscious, choices people make every day—to drive instead of walk, to stay indoors rather than visit a park, or to order in rather than meet friends at a local cafe—are profoundly shaped by the very design of the cities they inhabit. A revolutionary shift in urban and landscape design is now challenging the long-held conventions of city planning by placing human needs and daily routines at the absolute center of the creative process. This people-centric approach moves beyond mere functionality to actively foster community, promote individual well-being, and cultivate a deep, intuitive sense of place. It is a philosophy built on the understanding that the most effective cities are not just collections of buildings and roads but are living, breathing environments that intuitively guide residents toward healthier, more connected, and lower-impact lifestyles. By making positive life choices feel effortless, designers can transform the urban fabric into a powerful catalyst for a better quality of life for all.

The Core Philosophy of Intuitive Design

The primary objective for contemporary urban designers is to engineer environments where sustainable and healthy choices become the most instinctive and convenient options. This demands a deeply analytical approach to understanding the rhythms of daily human activity: how people commute from their homes, the destinations they frequent for work and leisure, the routes children take to school, and the types of spaces they seek for social interaction at various times of the day. By meticulously answering these fundamental questions, designers can strategically implement infrastructure such as interconnected walkways, dedicated bicycle lanes, accessible public parks, engaging playgrounds, and vibrant high streets that seamlessly align with natural human behavior. This method transcends the mere provision of amenities; it is about creating a cohesive network that supports and encourages a more active and engaged lifestyle without requiring conscious effort from the resident. The result is an urban landscape that feels less like an imposition and more like a natural extension of one’s own life.

This methodology is fundamentally about a tangible improvement in the quality of daily existence. People-centric design prioritizes exceptional connectivity, universal accessibility, and robust social infrastructure, recognizing that these are the building blocks of a strong and resilient community. Its goals are to strengthen community bonds, promote social inclusion, and cultivate a distinct sense of place through the creation of welcoming and thoughtfully designed environments. Within this framework, high-quality green spaces are not treated as mere aesthetic additions but as vital, functional components that deliver significant environmental benefits while simultaneously enhancing personal well-being and everyday enjoyment. As some of the world’s most livable cities have long demonstrated, this approach transcends pure utility to create places that actively support and enrich social interaction and the “lived experience,” a quality that is now being pursued by urban centers globally as they reconfigure their public spaces to better serve their inhabitants.

The Interconnected Triangle of Well-being, Mobility, and Sustainability

A crucial theme within this design philosophy is the mutually beneficial relationship between individual well-being, sustainable mobility, and overall urban sustainability. Thoughtfully planned design interventions in public spaces serve as the critical link connecting these three pillars. When a city is intentionally designed to encourage walking and cycling through safe, pleasant, and direct routes, it not only improves the physical and mental health of its residents but also directly reduces the carbon emissions and congestion that result from vehicular traffic. The primary challenge for designers, however, is to adapt these universal principles to a vast array of local climates, cultures, and contexts in ways that are both culturally relevant and environmentally sustainable over the long term. This requires a nuanced understanding that a successful design in one region cannot simply be replicated elsewhere without careful consideration of local nuances and lifestyles.

To address this, a deep and respectful understanding of local culture is paramount. The design must reflect how a specific population engages in outdoor recreation and activity, which can vary dramatically around the world. In Saudi Arabia, for example, the extreme daytime heat shifts the patterns of daily life, making the cooler evening and nighttime hours the primary period for social and recreational activity. Consequently, urban design must prioritize features like effective and atmospheric lighting, comfortable evening gathering spaces, and safe nocturnal navigation. Conversely, in regions across India, where intense heat and humidity are constants, the design of shared spaces often follows a different hierarchy, emphasizing smaller-scale, communal areas that support close-knit neighborhood life. Given that large-scale masterplans can take one to two decades to fully realize, this cultural attunement is essential for ensuring their long-term relevance and connection with the communities they are meant to serve.

A Methodological Shift From Top-Down to Bottom-Up

A significant evolution in urban planning involves shifting from a traditional top-down approach to a more human-scaled, bottom-up methodology that prioritizes the individual experience. Historically, masterplanning began with macro-level elements like major road systems, zoning regulations, and large-scale infrastructure, with the details of human life fitted in afterward. However, a more effective modern approach is to “flip the script” entirely. This means starting the design process at the most personal and intimate level: the home. Modern urbanism, in this view, is about making everyday life intuitive by removing the friction between convenient choices and those that are sustainable and healthy. The ultimate goal is for the better choice to also be the easier, more pleasant choice. This bottom-up process begins by considering the concept of “territoriality,” with the home serving as the central anchor of a person’s life and daily routines.

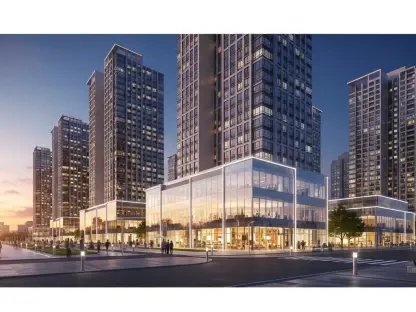

From this anchor, the design layers outward, planning the city around the tangible realities of daily life—how far people are willing to walk or cycle for daily needs, how they navigate their commute, and how safely and independently children can explore their own neighborhood. A masterplan is deemed truly successful when the tension between maintaining healthy habits and enjoying ease of movement is minimized or eliminated. This philosophy has been demonstrated in practice through diverse projects such as Bujairi Terrace in Diriyah, where an open-air retail and dining concept was developed within a rich heritage context. The design consciously moved away from a standard, air-conditioned mall, directly responding to how people live and socialize by using thoughtful planting, seating arrangements, and lighting to encourage human connection with nature and with each other, even in a challenging climate. This required a deep understanding that in hot climates, the public realm truly comes alive in the evening, necessitating a greater focus on shade, cooling technologies, and spatial comfort.

A Lasting Impact on Human Behavior

The conversation ultimately extended to the profound impact that human behavior has on our collective carbon footprint, a critical consideration for all built environment professionals. Design’s role in influencing this behavior was seen to operate on two key scales. The first was the macro or “landscape masterplanning” scale, which involved major strategic decisions about green corridors, transportation networks, and land use. The second was the micro scale, which encompassed the finer details of materiality, thermal comfort, shade strategies, and human-centric amenities. Comfort, accessibility, and functionality were identified as the key drivers for enabling healthy and sustainable habits. While designers could not control every external factor, they possessed a formidable toolkit to reduce the environmental impact of their projects. This included leveraging powerful tools like carbon sequestration through extensive planting, biophilia to connect people with nature, advanced soil management, biodiversity enhancement, and the creation of intelligent water systems. Design was not a “silver bullet” that could single-handedly force behavioral change. Rather, design created enabling systems—physical and social frameworks that made positive behavioral shifts both possible and attractive, allowing a new paradigm to emerge gradually over the years as projects became integrated parts of people’s lives.