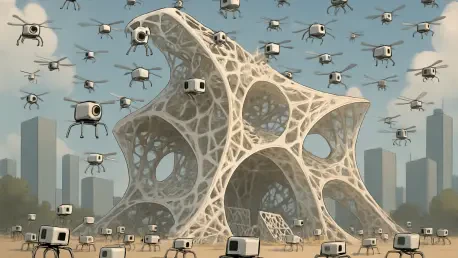

The prevailing vision of a “smart” building often involves a complex network of sensors and heavy mechanical parts, all tethered to a vulnerable, centralized control system; this model, while innovative, essentially adds a layer of technology onto a fundamentally static structure. A groundbreaking new concept, however, seeks to completely redefine our interaction with the built environment by transforming buildings from inert objects into dynamic, responsive organisms. Researchers have developed the “Swarm Garden,” a revolutionary approach to “living” architecture that employs a collective of small, interconnected robots to create surfaces capable of movement, adaptation, and environmental response. This breakthrough moves away from the traditional top-down control paradigm, instead drawing inspiration from the decentralized, collective intelligence seen in nature. By embedding a sort of nervous system directly into the building’s skin, this technology promises to turn passive structures into active participants in their surroundings, fundamentally altering how we design, inhabit, and interact with architectural spaces.

From Concept to Functional Reality

The Mechanics of Collective Intelligence

The foundational principle of the Swarm Garden is a departure from conventional robotics, embracing the concept of “swarm intelligence” that governs natural systems like ant colonies or schools of fish. In this model, there is no single “brain” or central controller issuing commands to the whole. Instead, the system’s complex, emergent behavior arises from the simple, localized interactions of numerous autonomous units. These units, called “SGbots,” are modular robots each equipped with a light sensor, a proximity sensor, and a radio for communicating only with their immediate neighbors. The movement of each SGbot is ingeniously simple and efficient; a soft actuator silently pulls a thin plastic sheet, causing it to buckle and “bloom” outward much like a flower. This mechanism is not only quiet and flexible but also inherently safe for human interaction. When hundreds of these bots act in concert, their individual blooming motions combine to create large-scale, coordinated transformations across the entire surface, all without a central processing unit dictating the overall pattern. This decentralized approach is the key to the system’s resilience and adaptability.

Resilience and Adaptation in Practice

To transition this innovative concept from theory to a tangible application, researchers conducted a crucial functional test by installing a network of 40 SGbots on an office window. The primary objective was to autonomously manage the flow of natural sunlight throughout the day, a common challenge in building design that often relies on cumbersome mechanical blinds or energy-intensive solutions. The swarm performed exceptionally, with the individual bots sensing the changing intensity of the sun and extending in unison to provide shade during the peak afternoon glare. As the sun began to set, the swarm seamlessly retracted, once again allowing natural light to fill the space. This experiment demonstrated not only the system’s effectiveness but also its remarkable resilience, a critical attribute for any real-world architectural component. To test this, several bots were intentionally disabled. Rather than causing a system-wide failure, the surrounding healthy units immediately compensated for the inactive bots, adjusting their own positions to maintain the integrity of the shaded area. This self-healing capability underscores the profound advantage of a decentralized network over a centralized one, proving its robustness for everyday, long-term use.

Exploring New Frontiers and Future Challenges

The Intersection of Art and Technology

Beyond its purely functional applications, the Swarm Garden technology was tested for its creative and interactive potential in a second experiment that blurred the lines between architecture, robotics, and performance art. A 36-bot array was installed in a public gallery, where it was programmed to engage directly with visitors. The installation transformed from a static surface into a dynamic, living entity that responded to human presence and movement. The swarm reacted to the simple hand gestures of onlookers, creating ripples and patterns across its surface. In a more complex demonstration of its capabilities, the system mirrored the movements of a dancer who was wearing a motion-tracking sensor. As the dancer moved, the swarm changed its shape and the color of its integrated LED lights in real time, creating a captivating visual dialogue between human and machine. This experiment powerfully showcased the system’s potential as a responsive partner in artistic expression, fostering a dynamic interplay that made the entire installation feel sentient and alive, opening up new possibilities for interactive public spaces and immersive experiences.

Charting the Path to Widespread Adoption

The successful demonstrations of the Swarm Garden underscored a future where building facades could intelligently manage sunlight, heat, and airflow without complex and failure-prone mechanical systems, leading to more sustainable and energy-efficient architecture. The core principles of this decentralized robotic system had clear implications beyond buildings, suggesting potential advancements in smart materials, interactive art, and even self-reconfiguring structures for disaster-resilient infrastructure. However, the system remained a proof of concept, and significant challenges had to be addressed before widespread adoption could be considered. The primary concern was material durability, as the thin plastic sheets were subjected to considerable stress from the repeated “blooming” motion, raising questions about their long-term viability. Future research was therefore focused on developing more resilient and sustainable materials, including explorations of energy-efficient designs inspired by kirigami, the Japanese art of paper cutting. The development team planned to collaborate with architects to evaluate the feasibility of long-term deployments in a variety of real-world settings to move the technology from the laboratory into the fabric of our cities.