In the ongoing effort to balance the urgent need for urban housing with the unshakeable principles of public safety, a significant divergence in building philosophy has emerged between the City of Vancouver and the provincial government of British Columbia. The Vancouver City Council has decisively approved two innovative staircase designs for multi-family buildings, pointedly rejecting a recent and highly contentious change to the B.C. Building Code that permitted a single-egress staircase model. This move underscores a critical debate in modern urban planning: how to increase housing density efficiently without compromising the safety of residents and first responders. The city’s action is not merely a bureaucratic footnote but a firm statement on where its priorities lie, championing a layered approach to safety that stands in stark contrast to the province’s more streamlined, yet heavily criticized, solution. This decision sets a precedent for how municipalities can assert local control over building standards to address unique urban challenges and safety considerations.

A Provincial Mandate Met with Widespread Opposition

The controversy began in August 2024, when the provincial government approved a new single-staircase model for residential buildings up to six stories high, intending to facilitate denser housing construction on smaller, more constrained lots. However, this policy was immediately met with a unified front of opposition from B.C. fire officials, who raised serious alarms about the inherent risks. Their primary argument centered on the elimination of safety redundancy. In a fire, having two separate escape routes is a cornerstone of building safety, ensuring that if one stairwell is compromised by smoke or flames, another remains accessible for occupants to evacuate and for firefighters to enter and conduct rescue operations. Critics argued that a single staircase creates a single point of failure, a dangerous bottleneck that could trap residents and dangerously hamper firefighting efforts. This expert consensus from those on the front lines of emergency response cast a long shadow over the provincial code, framing it as a regressive step that prioritized development speed over fundamental life-safety principles.

Beyond the stark safety warnings from fire professionals, the provincial single-stair design also failed to gain traction with the very builders and developers it was meant to entice. While the concept of saving space was initially appealing, the practical realities of the design proved to be economically unviable and technically complex. The provincial code mandated a suite of expensive and sophisticated safety features to compensate for the missing second staircase. These included significantly wider stairs, elaborate air pressurization systems designed to control smoke movement, backup emergency generators to power these systems during an outage, and enhanced sprinkler systems. Developers quickly determined that the high costs of installing and maintaining this complex equipment outweighed the benefits of the saved floor space. Furthermore, the reliance on long-term, flawless maintenance of these active systems introduced a level of uncertainty that many were unwilling to accept, leading to a near-total lack of applications for the new design and rendering the provincial initiative largely ineffective.

Vancouver Forges an Independent Path

Operating under the authority of its own distinct building by-law, the City of Vancouver was uniquely positioned to chart its own course, independent of the provincial mandate. Following the province’s announcement, the city initiated its own round of consultations, where local fire officials unequivocally echoed the safety concerns voiced by their counterparts across British Columbia. They reinforced the critical importance of redundant egress routes and expressed deep reservations about the reliability of a single-stair system, even one bolstered by advanced technology. In response to this expert feedback, the Vancouver City Council took a proactive stance, directing city staff to collaborate with architects, engineers, and fire safety experts to develop workable local solutions. This collaborative process was designed to achieve the shared goal of housing density while upholding the city’s stringent safety standards, culminating in the formal rejection of the provincial model in favor of two thoughtfully engineered, made-for-Vancouver alternatives that successfully secured the crucial endorsement of fire officials.

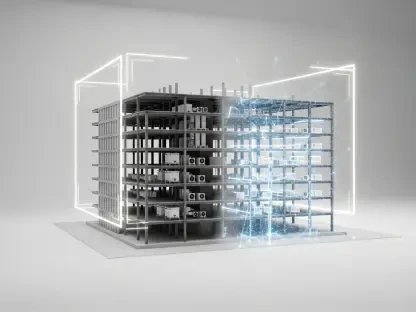

The first of the two approved designs, the “Space Efficient Scissor Stairs,” masterfully addresses the dual needs of safety and spatial economy. This innovative configuration features two completely separate, fire-proofed staircases ingeniously intertwined within the footprint of a single, larger stairwell enclosure. Functionally, it provides two distinct and protected escape routes, ensuring that the principle of redundancy is fully restored. Should one staircase become impassable due to smoke or fire, residents and emergency crews have a clear, alternative path. For developers, this design offers a significant advantage over traditional two-stair layouts by consuming considerably less floor area. This efficiency translates directly into lower construction costs and maximizes the amount of usable, revenue-generating space that can be dedicated to housing units, presenting a compelling and balanced solution that satisfies both safety regulators and the construction industry.

A New Standard for Urban Density

The second approved alternative, the “Single Exterior Exit Stair and Passageway,” offers a different but equally effective approach to ensuring resident safety while maximizing interior space. This typology moves the building’s primary circulation corridor and its single staircase to the exterior of the structure. The open-air nature of this design is its key safety feature, as it effectively prevents the dangerous accumulation of smoke in the primary escape route—a critical risk factor in building fires. This natural ventilation ensures the path of egress remains clear for evacuating occupants. From a development perspective, relocating the corridor and stairs to the outside frees up a substantial amount of internal floor space for the creation of more housing units. To ensure this design does not compromise safety, the city’s by-law places a strict limit on the number of suites allowed per floor, a crucial measure that guarantees the single exterior staircase has sufficient capacity to accommodate a full-scale evacuation in an emergency.

By thoughtfully rejecting the province’s contentious single-stair model, Vancouver’s City Council effectively established its own forward-thinking standard for mid-rise residential construction. The city’s decision to instead adopt two distinct, safety-focused alternatives represented a strong affirmation of a consensus viewpoint shared by fire professionals and developers alike. This outcome demonstrated that strategies for increasing housing density must be firmly grounded in proven fire-safety principles and must also be economically viable for the builders tasked with constructing new homes. This decisive action set a clear precedent, illustrating how a major municipality could leverage its autonomy to innovate its own building codes, creating a tailored solution that addressed the local need for both enhanced safety and increased housing supply.