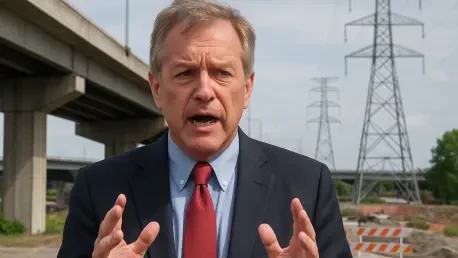

A fundamental transformation in how global infrastructure is governed has become a critical necessity, according to Richard Threlfall, the newly appointed chair of the charitable organization Engineers Against Poverty. He posits that the engineering, infrastructure, and construction sectors must spearhead this change to address a cascade of interconnected crises, including abject poverty, staggering economic waste, and catastrophic climate change. This perspective, shaped by a deep understanding of both emerging and developed economies, suggests that effective, transparent, and sustainable governance is the single most important lever for progress. The diagnosis is clear: systemic failures in project delivery are hindering human development and environmental sustainability on a global scale, but a clear, actionable framework for reform offers a viable path forward. This call to action is not merely a technical proposal but a profound moral argument for a more accountable and efficient future.

The Foundational Role of Infrastructure

Infrastructure serves as the very foundation of modern civilization, yet in developed nations, its constant presence often leads to it being taken for granted. This reality stands in stark contrast to the daily experience in many parts of Africa, Central and South America, and the Asia-Pacific region, where the absence of basic systems perpetuates a cycle of systemic poverty. A compelling case is made that providing essential infrastructure—such as clean water, sanitation, and reliable transportation—is arguably the most direct and rapid pathway to lifting the nearly 800 million people still living in abject poverty into a state of dignity and economic opportunity. This reframing elevates the mission of infrastructure delivery from a purely technical or economic exercise to a profound moral and social imperative. It challenges the global community to recognize that access to these fundamental services is a prerequisite for human flourishing and a cornerstone of equitable global development.

A central dilemma confronting the world is the massive chasm between its vast infrastructure needs and its finite resources, a problem that impacts both emerging and developed markets alike. This scarcity makes any form of waste not just an inefficiency but a morally indefensible act that directly impedes progress. A staggering estimate from McKinsey quantifies this problem, suggesting that a significant portion of the world’s infrastructure costs approximately 40% more than it should. This statistic is skillfully reframed not as a sunk cost but as a monumental opportunity. By systematically eliminating this 40% waste through better governance and efficiency, societies could generate 40% more critical infrastructure—whether sanitation facilities, clean water projects, or rural transportation networks—for the exact same level of investment. This highlights how systemic inefficiency is not a passive issue but an active barrier preventing the alleviation of human suffering and the advancement of global development goals.

A New Framework for Governance and Transparency

According to this analysis, the root cause of this pervasive waste and inefficiency is a systemic and widespread failure in governance. It is noted that “the central governance of infrastructure is often quite weak and disaggregated” across most markets globally, creating vulnerabilities that lead to poor outcomes. This is precisely where the work of Engineers Against Poverty becomes critical. The organization’s core mission is to collaborate directly with governments, civil society organizations, and private sector entities to build robust frameworks for infrastructure delivery. The primary objective is to ensure that projects are managed with maximum efficiency, complete transparency, and long-term sustainability, all while maintaining an unwavering intolerance for corruption. This proactive approach seeks to build capacity from within, empowering local stakeholders to demand and deliver better value from public investments and create a legacy of accountability.

A major vehicle for this mission is the organization’s role in hosting the secretariat for CoST, the Construction Sector Transparency Initiative. CoST is a global non-profit, predominantly funded by international bodies, dedicated to enhancing transparency, public participation, and accountability in infrastructure projects. A powerful real-world example of its impact comes from its work in Uganda. A 2017 study revealed that public procuring entities were disclosing only 34% of the key data points required by the CoST Infrastructure Data Standard. Following the program’s intervention, which advocated for public data disclosure as a means to flag risks and demand accountability, a subsequent review in 2018 showed a dramatic improvement, with the disclosure rate climbing to 62%. This demonstrates that data and digitization are “absolutely fundamental” to this process, providing the structural framework for transparency and empowering citizens to hold decision-makers accountable for public funds.

Connecting Transparency to Environmental Sustainability

The argument for enhanced transparency and governance extends far beyond economic efficiency to address the pressing and existential issue of climate change. Speaking in the context of COP30, it is underscored that scientific urgency is paramount, as the world is on track to surpass the 1.5°C warming threshold within just four years—a critical tipping point that could trigger an “exponential decline” of vital ecosystems. The infrastructure sector, in this view, has a dual responsibility of immense proportions. First, it must rapidly and aggressively decarbonize its own operations to mitigate its significant environmental footprint. Second, it must adapt existing assets and design new ones to withstand the inevitable impacts of climate change, such as extreme heat, prolonged drought, and severe flooding, which disproportionately affect the world’s most vulnerable nations and populations who have contributed least to the problem.

A paradox exists wherein global emissions continue to rise despite the remarkable success of renewable energy technologies. This trend is fueled by the explosive growth of energy-intensive data centers for artificial intelligence, coupled with population growth and rising prosperity in major economies. This reality necessitates a global pivot toward supporting “green, sustainable growth” in every sector. Within this context, a profound point about professional responsibility is articulated. While acknowledging that no single engineer is to blame for the fact that infrastructure is responsible for an estimated 80% of global carbon emissions, it is asserted that the industry uniquely possesses the skills, knowledge, and capabilities to solve the problem at speed. This gives the profession an “outsized responsibility” that is directly proportional to its “outsized ability to make a difference,” creating a moral obligation to lead the global transition toward a sustainable future.

Applying the Principles in a Developed Context

A significant portion of this analysis was dedicated to applying these international lessons directly to the United Kingdom, illustrating that the principles of transparent governance and efficiency are universally critical. The UK faces its own formidable challenges, including growing regional economic inequality, severe budgetary constraints, and a history of inefficient public project delivery. A key historical weakness was pinpointed as a “lack of holistic, system-level infrastructure planning,” which has often resulted in disjointed and suboptimal outcomes. While progress had been made by bodies like the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC) in improving strategic planning, a persistent “gap” remained between the NIC’s well-researched recommendations and their actual implementation by the government, a divide that a new national authority was intended to bridge.

Ultimately, the power to drive meaningful change in the UK rested with the “handful of big buyers of infrastructure”—primarily government entities and large utility companies. The proposed mechanism for this change mirrored the strategy employed in emerging markets: radical transparency. This included advocating for the full public disclosure of project pipelines, procurement processes, bidding information, and ongoing project progress against established cost and scope benchmarks. By making this information public data, a new ecosystem of accountability could be created. This system allowed for direct comparison between what was promised and what was delivered, a process that had the power to transform the sector into one that was far more cost-effective, accountable, and equitable for all citizens.