With the Building Safety Act 2022 fundamentally reshaping liability in the construction sector, historical projects are coming under intense legal scrutiny. The £30 million lawsuit between Taylor Wimpey and Vinci over the Victoria Wharf development in Cardiff is a landmark case, illustrating the Act’s far-reaching consequences. It brings to the forefront complex issues of proving historical negligence, the devastating real-world impact of fire safety defects, and the intricate corporate histories that can complicate accountability. We sat down with construction expert Luca Calaraili to dissect the technical, legal, and logistical challenges this case represents for the entire industry.

The Building Safety Act 2022 extended liability to 30 years, enabling this £30m lawsuit over the Victoria Wharf project. Can you walk me through the typical legal steps and challenges involved in proving workmanship from 2008 was professionally negligent under the Defective Premises Act?

The Act was a seismic shift, breathing new life into claims that were long thought to be statute-barred. The biggest challenge in a case like this is the passage of time. You’re trying to reconstruct events from over a decade ago. The first step is extensive forensic investigation—literally peeling back the layers of the building to see what’s there versus what should have been there according to the 2002 Building Regulations. This involves meticulous documentation, but paper trails from 2008 can be fragmented or lost entirely. You then have to prove that the work fell below the standard of a “workmanlike or professional manner” for that specific era, not today’s much stricter standards. It’s a painstaking process of linking the physical defects found today directly back to the actions, or inactions, of the original contractor, Taylor Woodrow, and proving it wasn’t due to subsequent alterations or poor maintenance.

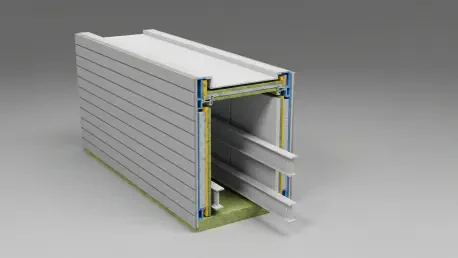

The claim cites missing cavity barriers and non-compliant wall systems using Kingspan insulation. From a fire safety engineering perspective, how do these specific defects combine to create a dangerous situation, and what metrics are used to assess that risk in a building like Victoria Wharf?

It’s a textbook example of a catastrophic combination. Think of missing cavity barriers as open highways for fire. They are meant to compartmentalize the hidden voids within a building’s walls, stopping flames and superheated gases from spreading unseen from one apartment to the next, or from floor to floor. When they’re missing, a small fire can become an inferno engulfing the entire building with terrifying speed. Now, add in the Kingspan insulation, which was cited as not being a “material of limited combustibility.” This material can contribute to the fire load, accelerating the blaze and releasing toxic smoke. On top of that, the unprotected structural steelwork is the building’s skeleton. In a fire, that steel heats up, loses its integrity, and can lead to structural collapse. You have a fire that spreads fast, is fueled by its own walls, and is attacking the very structure holding it up—it’s an incredibly dangerous cocktail that makes a building “not fit for habitation.”

Remediation for Victoria Wharf’s seven towers is a £32.5m, three-year project. Could you describe the logistical challenges of retrofitting occupied buildings on this scale? For example, what are the key steps involved in managing resident displacement and ensuring their safety during the work?

The scale of this operation is immense; you’re essentially performing open-heart surgery on seven occupied towers simultaneously. The logistical complexity is staggering. First, you have to erect scaffolding and wrap the entire building, which immediately creates a sense of living in a cage for the 450 households. The work itself involves stripping the external facade right back to the structure, exposing apartments to the elements and creating constant, unavoidable noise and dust. The human element is the most challenging part. You have to manage the anxiety and disruption for hundreds of residents over three years. This requires a phased approach, working on elevations or sections of the building at a time, but it often necessitates moving residents into temporary accommodation, which is a logistical and financial nightmare in itself. All the while, you must maintain safe emergency escape routes and fire-watch patrols because, ironically, the building is at its most vulnerable during the remediation process.

Taylor Wimpey and Taylor Woodrow were part of the same group until the 2008 sale to Vinci, just two months after the project finished. How might this shared history impact the legal proceedings? For instance, what kind of indemnification clauses from that sale might become central to Vinci’s defense?

This corporate entanglement turns a complex construction dispute into a legal chess match. Vinci’s defense will almost certainly revolve around the specifics of the Sale and Purchase Agreement from September 2008. They will argue that they purchased the Taylor Woodrow entity but that the historical liabilities, especially for a project completed just two months prior under a different parent company, were either retained by the Taylor Wimpey group or were capped at a certain value. The lawyers will be digging through that document for indemnification clauses and warranties. Did the seller, Taylor Wimpey, provide a warranty that all completed works were defect-free? Did they agree to indemnify the buyer, Vinci, against any future claims arising from past projects? The timing is so tight that it’s almost certain this was a key point of negotiation during the sale, and the wording of those clauses will be the battleground on which much of this £30m case is fought.

What is your forecast for the construction industry? Given the Building Safety Act, do you anticipate a surge in similar multi-million-pound lawsuits over historical defects, and how might this fundamentally change the relationships and risk-sharing agreements between developers and their main contractors going forward?

Absolutely. This case is the tip of the iceberg. The Building Safety Act’s 30-year retrospective liability period has opened a floodgate of latent claims. Developers who have signed government remediation pledges, like Taylor Wimpey did under the Welsh Government’s pact, are now on the hook for hundreds of millions in repair costs. Their first and most logical step is to turn to their original supply chains—the contractors and consultants—to recoup those staggering sums. We are going to see a tidal wave of litigation as these costs are passed down the line. Looking forward, this will permanently alter the risk landscape. New contracts will be far more stringent, with developers demanding iron-clad warranties and extensive indemnities. In response, contractor insurance premiums will skyrocket, and those costs will inevitably be passed on, potentially making new developments more expensive. The ultimate, and hopefully positive, outcome will be a cultural shift toward meticulous record-keeping and a much higher standard of quality control, because the financial consequences of getting it wrong are now too vast to ignore.